"Marketing research does not make decisions and it does not guarantee success". Marketing managers may seek advice from marketing research specialists, and indeed it is important that research reports should specify alternative courses of action and the probability of success, where possible, of these alternatives. However, it is marketing managers who make the final marketing decision and not the researcher

The purpose of the research

It is not at all unusual for marketing managers to neglect to tell the researcher the precise purpose of the research. They often do not appreciate the need to do so. Instead, they simply state what they think they need to know. This is not quite the same thing. To appreciate the difference consider the case of the marketing research agency which was contacted by the International Coffee Organization (ICO) and asked to carry out a survey of young people in the age group 15-24. They wanted information on the coffee drinking habits of these young people: how much coffee they drank, at what times of day, with meals or between meals, instant or ground coffee, which other beverages they preferred and so on. In response, the research organization developed a set of wide-ranging proposals which included taking a large random sample of young people.

In fact much of the information was interesting rather than important. Important information is that information which directly assists in making decisions and the ICO had not told the research company the purpose of the research. The initial reason for the study had been a suspicion, on the part of the ICO, that an increasing percentage of young people were consuming beverages other than coffee, particularly soft drinks, and simply never developed the coffee drinking habit. Had this been explained to the research company then it is likely that their proposals would have been radically different. To begin with, the sample would have been composed of 15-24 year old non-coffee drinkers rather than a random sample of all 15-24 year olds. Second, the focus would have been non-coffee drinking habits rather than coffee drinking habits.

Unless the purpose of the research is stated in unambiguous terms it is difficult for the marketing researcher to translate the decision-maker's problem into a research problem and study design.

Suppose that the marketing manager states that he needs to know the potential market for a new product his/her organisation has been developing. At first glance this might appear to meet all of the requirements of being clear, concise, attainable, measurable and quantifiable. In practice it would possibly meet only one of these criteria, i.e. it is concise!

Here is another case to be considered. A small engineering firm had purchased a prototype tree-lifter from a private research company. This machine was suitable for lifting semi-mature trees, complete with root-ball intact, and transplanting such trees in another location. It was thought to have potential in certain types of tree nurseries and plantations.

The problem with the objective is that the marketing manager needs to know the potential market for the new tree-lifter is that it is not attainable. One could find out how many tree-lifters were currently being sold but this is not the same as the objective set by the marketing manager. The market potential for any new brand is a function of at least 4 things, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The components of market potential

Step 1: Problem definition

The point has already been made that the decision-maker should clearly communicate the purpose of the research to the marketing researcher but it is often the case that the objectives are not fully explained to the individual carrying out the study. Decision-makers seldom work out their objectives fully or, if they have, they are not willing to fully disclose them. In theory, responsibility for ensuring that the research proceeds along clearly defined lines rests with the decision-maker. In many instances the researcher has to take the initiative.

In situations, in which the researcher senses that the decision-maker is either unwilling or unable to fully articulate the objectives then he/she will have to pursue an indirect line of questioning. One approach is to take the problem statement supplied by the decision-maker and to break this down into key components and/or terms and to explore these with the decision-maker. For example, the decision-maker could be asked what he has in mind when he uses the term market potential. This is a legitimate question since the researcher is charged with the responsibility to develop a research design which will provide the right kind of information. Another approach is to focus the discussions with the person commissioning the research on the decisions which would be made given alternative findings which the study might come up with. This process frequently proves of great value to the decision-maker in that it helps him think through the objectives and perhaps select the most important of the objectives.

Research forms a cycle. It starts with a problem and ends with a solution to the problem. The problem statement is therefore the axis which the whole research revolves around, beacause it explains in short the aim of the research.

1 WHAT IS A RESEARCH PROBLEM?

A research problem is the situation that causes the researcher to feel apprehensive, confused and ill at ease. It is the demarcation of a problem area within a certain context involving the WHO or WHAT, the WHERE, the WHEN and the WHY of the problem situation.

There are many problem situations that may give rise to reseach. Three sources usually contribute to problem identification. Own experience or the experience of others may be a source of problem supply. A second source could be scientific literature. You may read about certain findings and notice that a certain field was not covered. This could lead to a research problem. Theories could be a third source. Shortcomings in theories could be researched.

Research can thus be aimed at clarifying or substantiating an existing theory, at clarifying contradictory findings, at correcting a faulty methodology, at correcting the inadequate or unsuitable use of statistical techniques, at reconciling conflicting opinions, or at solving existing practical problems.

2 IDENTIFICATION OF THE PROBLEM

The prospective researcher should think on what caused the need to do the research (problem identification). The question that he/she should ask is: Are there questions about this problem to which answers have not been found up to the present?

Research originates from a need that arises. A clear distinction between the PROBLEM and the PURPOSE should be made. The problem is the aspect the researcher worries about, think about, wants to find a solution for. The purpose is to solve the problem, ie find answers to the question(s). If there is no clear problem formulation, the purpose and methods are meaningless.

Keep the following in mind:

- Outline the general context of the problem area.

- Highlight key theories, concepts and ideas current in this area.

- What appear to be some of the underlying assumptions of this area?

- Why are these issues identified important?

- What needs to be solved?

- Read round the area (subject) to get to know the background and to identify unanswered questions or controversies, and/or to identify the the most significant issues for further exploration.

The research problem should be stated in such a way that it would lead to analytical thinking on the part of the researcher with the aim of possible concluding solutions to the stated problem. Research problems can be stated in the form of either questions or statements.

- The research problem should always be formulated grammatically correct and as completely as possible. You should bear in mind the wording (expressions) you use. Avoid meaningless words. There should be no doubt in the mind of the reader what your intentions are.

- Demarcating the research field into manageable parts by dividing the main problem into subproblems is of the utmost importance.

3 STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

The statement of the problem involves the demarcation and formulation of the problem, ie the WHO/WHAT, WHERE, WHEN, WHY. It usually includes the statement of the hypothesis.

5 CHECKLIST FOR TESTING THE FEASIBILITY OF THE RESEARCH PROBLEM

Step.I: Problem Definition

the decision maker holds the initial responsibility of deciding that

there might be a need for the services of a researcher in addressing a recognized decision

problem or opportunity. Once brought into the situation, the researcher begins the problem

definition process by asking the decision maker to express his or her reasons for thinking

that there is a need to undertake research. Using this type of initial questioning procedure,

researchers can begin to develop insights as to what the decision maker believes to be the

problem. Having some basic idea of why research is needed focuses attention on the circumstances

surrounding the problem. The researcher can then present a line of questions

that can lead to establishing clarity between symptoms and actual causal factors. One

method that might be employed here is for researchers to familiarize the decision maker

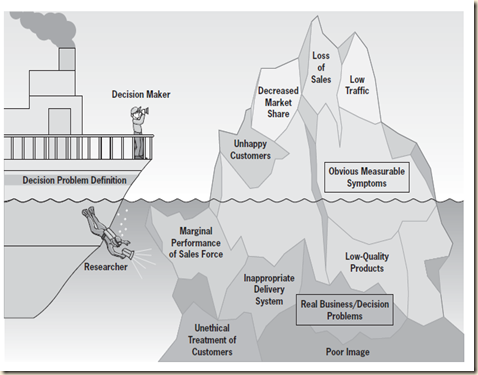

with the iceberg principle

Iceberg principle

Principle that states that

only 10 % of most problems are visible to

decision makers, while the remaining 90 %

must be discovered through research.

Once the researcher understands the overall problem situation, he or she must work with

the decision maker to separate the root problems from the observable and measurable

symptoms that may have been initially perceived as being the decision problem. For example,

many times managers view declining sales or reduction in market share as problems.

After fully examining these issues, the researcher may see that they are the result of more

concise issues such as poor advertising execution, lack of sales force motivation, or even

poorly designed distribution networks. The challenge facing the researcher is one of clarifying

the real decision problem by separating out possible causes from symptoms. Is a

decline in sales truly the problem or merely a symptom of bad advertising practices, poor

retail choice, or ineffective sales management?

Once the decision problem at hand is understood and specific information requirements are

identified, the researcher must redefine the decision problem in more scientific terms.

A hypothesis is basically an unproven statement of a research question in a testable

format.

Step.II: Set research objectives

Definition of Research Objectives

Marketing Research Objectives: the specific bits of knowledge that need to be gathered to close the information gaps highlighted in the research problem.

Stated in action terms

Serve as a standard to evaluate the quality and value of the research

Objectives should be specific and unambiguous

Examples:

To measure the number of college freshmen at UAH

To assess viewer recall of our ad campaign

To describe the segments of the marketplace

Putting It All Together

Management Problem Expressed in Terms of Research Questions and Hypotheses

Situation: A small retail specialty store featuring men’s casual wear in Southern California was concerned

about its trends in low traffic and sales figures. Management was unclear about what the store’s retail

image was among consumers.

MANAGEMENT’S INITIAL DECISION PROBLEMS

Should any of my current store/product/service/operation strategies be evaluated and possibly modified

to increase growth in the store’s revenue and market share indicators? Do merchandise quality, prices, and

service quality have an impact on customer satisfaction, in-store traffic patterns, and store loyalty images?

REDEFINED AS RESEARCH QUESTIONS

What are the shopping habits and purchasing patterns among people who buy men’s casual wear? That is,

Where do these people normally shop for quality men’s casual wear?

When (how often) do they go shopping for quality men’s casual wear?

What types of casual wear items do they like to shop for (purchase)?

Whom do they normally purchase men’s casual wear for?

How much (on average) do they spend on men’s casual wear?

What store/operation features do people deem important in selecting a retail store in which to shop for

men’s casual wear?

How do known customers evaluate the store’s performance on given store/operation features compared to

selected direct competitors’ features?

REDEFINED AS RESEARCH HYPOTHESES

There is a positive relationship between quality of merchandise offered and store loyalty among customers.

Competitive prices have greater influence on generating in-store traffic patterns than do service quality features.

Unknowledgeable sales staff will negatively influence the satisfaction levels associated with customers’ instore

shopping experiences.

RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

To collect specific attitudinal and behavioral data for identifying consumers’ shopping behavior,

preferences, and purchasing habits toward men’s casual wear.

To collect specified store/product/service/operation performance data for identifying the retailer’s

strengths and weaknesses which could serve as indicators for evaluating current marketing and

operational strategies.

To collect attitudinal data for assessing the retailer’s current overall image and reputation as a retail men’s

casual wear specialty store.

---------------

Management Problem

Placement office has noticed, while major companies make annual recruiting visits to campus for engineers, not many national or local companies are formally recruiting business majors through the placement office

Why? How do we address this?

Marketing Research Problems

Why are companies not taking advantage of the resources that the placement service offers? Are companies going around the service?

Are companies aware of the UAH placement service?

Are companies aware of the reputation of the UAH Business School?

What kind of things might generate more recruiting activity?

Marketing Research Objectives

To determine to what extent companies are aware of the UAH placement service

Determine whether companies, especially locals, are aware of the strong reputation of the UAH Business School

To determine whether a quarterly newsletter highlighting UAH business programs and students might generate more recruiting activity.

Another Example

Management Problem

What price should we charge for our new product?

Research Problem

What are our costs of production and marketing (COGS)?

What are our pricing objectives and position in the market?

What price does similar types of products sell for?

What is the perceived value of our product in the marketplace?

Are there any norms or conventional practices in the marketplace (e.g., customary prices, continual discounting)

Research Objectives

To assess the costs involved in producing and selling our product

To determine corporate objectives and their implications for pricing

To examine current prices for direct and indirect competition

To determine potential customer reaction to various prices and their perception of the benefits of owning the product

Exercise

For the following management problems, identify the underlying research problems and a couple of research objectives.

- “Should our retail chain offer online shopping?”

- “What advertising media should we use to reach our market?”

- “How do we get more people to attend our outdoor festival/event?”

- “Should we build a new warehouse to store our excess inventory?”

- How can we increase customer retention?”

- “Should the amount of in-store promotion for an existing product line be increased?”

- “Should the compensation package be changed to better motivate the sales force?”

-------------

MARKETING RESEARCH MIX

The term

Marketing research mix (or the "MR Mix") was created in 2004 and published in 2007 (Bradley - see references). It was designed as a framework to assist researchers to design or evaluate marketing research studies. The name was deliberately chosen to be similar to the

Marketing Mix - it also has four Ps. Unlike the marketing mix these elements are sequential and they match the main phases that need to be followed. These four Ps are: Purpose; Population; Procedure and Publication.

If a business wants to make a product's total sales grow, it must carefully consider how best to extend its life cycle.

If a business wants to make a product's total sales grow, it must carefully consider how best to extend its life cycle.

Everything about the café needs to reflect the requirements of the target market. For example, the menus are carefully tailored to the requirements of the target audience at different times of the day. The savoury menu contains freshly baked baguettes with innovative fillings and hot panini. The cake menu includes a range of fresh cakes and there is a wide choice of ice-creams all served with Cadbury's chocolate.

Everything about the café needs to reflect the requirements of the target market. For example, the menus are carefully tailored to the requirements of the target audience at different times of the day. The savoury menu contains freshly baked baguettes with innovative fillings and hot panini. The cake menu includes a range of fresh cakes and there is a wide choice of ice-creams all served with Cadbury's chocolate.